The club meets 356 mod-father Rod Emory, a third generation Porsche-phile whose West Coast workshop is quietly re-writing the rulebook.

Words: Julian Milnes

Photos: Emory Motrosports

When it came to career paths, Rod Emory didn’t really have a choice. Growing up in California, with a grandfather who worked as a master craftsman rebuilding 356s and 911s in the ’60s, and a father who had the foresight to start a retro Porsche parts business in the ’70s, Rod’s destiny was pretty much mapped out.

“I would spend my summers from eight years old with my grandfather and my uncle, learning how to do metal work and body work, and ultimately how to restore cars. Along with that, my dad had all these great ideas within the car arena, including hot-rodding 356s,” remembers Rod.

At just 16 years of age he completed his first Outlaw, a restoration of a ‘53 356, utilising a small mechanic’s bay at the back of his father’s warehouse. “I had a really early start and great mix of experience, taking the practical restoration skills from my grandfather and uncle, and combining them with my dad’s ideas about design. It’s served me well,” he says.

Now 43, Rod has been building cars professionally for nearly 30 years, having established an early clientele while he was still in high school. He has now restored and built over 150 vehicles from the ground up.

Learning curves

“My grandfather taught me a lot”, says Rod. “He told me to modify everything but make it look like it hadn’t been customised. That was his secret to success – the subtle custom car.”

“When you looked at his cars it was hard to pick up on all the understated detail. His approach wasn’t like a typical custom shop that would just chop the top. He would go the hard route – channelling or sectioning the body, making it look thinner or adjusting and removing body lines. So working with him and my uncle, I learnt the physical skills, but also how to look at a car and make subtle adjustments to the lines, evolving the design.”

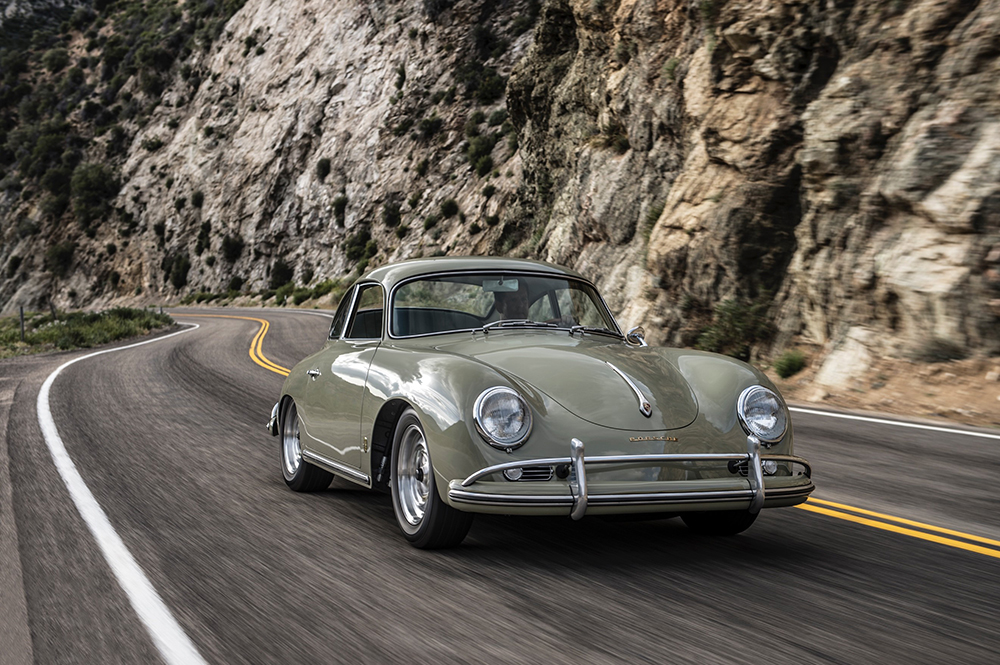

Now, when you look at one of Rod’s creations, you see a Porsche, but focus in and you begin to identify various tweaks and alterations that evolve and enhance the original design.

“I tend to draw from Porsche’s early racing heritage, the Spyders, the early Formula cars, all the way back to the pre-war cars,” says Rod. “All the early swoopy-lined cars from that era help me draw inspiration; they’re just so sexy and smooth. I’m not a pen and paper artist, I don’t like heavily sketched or rendered cars, I tend to visualise what I want, then start creating it in metal. I’m more of a sculptor than an illustrator.”

Pulling power

Rod built his first Special in 1998 – based on a ’64 cabriolet. Drawing inspiration from the early Porsche Le Mans cars, its ultimate purpose was as a vintage race car. “I wanted to build a car that had every aspect modified, as if Porsche had continued building the 356 after 1965. I took a ’64/’65 cabriolet and changed everything, even adding modern suspension. I used all the rear of a 1987 944 Turbo S, including Brembo brakes. It was far more than just the aesthetics.”

Once it was complete, Rod hooked a camping trailer on the back and, with his wife and three-month-old son on board, took off on a road trip. Porsche’s 50th anniversary at the Monterey Motorsports Reunion would be the first stop.

“The reaction was really something, people had already seen a few of my creations but nobody had seen anything like this. They didn’t know where it came from. Some thought it was an early prototype 356,” recalls Rod. “When I pulled into the paddock at Laguna Seca there was a big crowd around the car and a number of official Porsche guys from Germany in attendance. One turned to his colleagues and asked: ‘When did we build this car?’ For me, at 22, to have that reaction was confirmation I was on the right track.”

At that point, Rod’s primary focus was building vintage race cars, and from 1998 to 2008 he’d also take clients and their vehicles racing all over the country. “I was building about 10 cars a year, mostly vintage race cars, but I’d also build a couple of Specials and 356 Outlaws,” says Rod. “Then in 2007 I really started pushing towards developing a solid platform for the 356 I build today, focusing more on building road-going versions.”

Scaling up

Today in the Emory Motorsports workshop in North Hollywood, there are 10 employees and typically 12 cars in various stages of renovation, with another 20 on the waiting list. All are set to be transformed into Outlaw 356s or more complex Specials. It takes around 12 months to complete the transformation, with one finished each month for delivery to the customer. Each of the guys in the workshop has their speciality area in which Rod has trained them.

“Each car gets completely disassembled. The paint is stripped off and we do all the rust repair and chassis modifications, body modifications and custom work, then the paint, assembly, testing and driving,” Rod explains.

He prefers to save a car than take one that has already been restored. The process of restoring a body back to its original state is around six months, with the biggest time commitment being the sheet metal work, the rust repair and the chassis modifications.

“The greatest challenge with these cars,” Rod continues “is their age – the deterioration and the rust. The cars we’re starting with aren’t your full concours donor cars. I normally start with cars that many people would normally shy away from because they need extensive metal work and rust repair to bring them back.” And that’s only half the challenge. “All the cars I do have up to three times as much power and better brakes, so you have to do a number of things to stiffen up the chassis – there’s a lot of work behind the scenes.”

Customer satisfaction

With such a specialist build, customer involvement is crucial to ensure the end product ticks all the boxes, especially as the cost is between $250,000 and $300,000 before you factor in a donor car, which can set you back a further $80,000.

“When a client approaches me, I firstly determine what model they like the best. Is it a speedster, a roadster, a coupe or cabriolet? Then I interview them for a while to determine how they plan to use the car. Is it for the track or long distances? It helps me gain a better understanding of the type of car I should build.”

From there Rod puts together an outline of the car that covers 99 per cent of the bases and options. Then comes the all-important colour choice, which, once decided by the customer, is then broken down into a further four hues to ensure it’s just right. However, there are limits to customer requests.

“If you give them the freedom to choose everything, you’ll have something that will end up only suitable for the circus,” Rod says ruefully. “So I tend to steer the overall direction, so the design is balanced and it’ll have long-term value.”

“That said, I did get a request a few years ago for an all-wheel drive 356 from a customer in New Hampshire so he could drive it all year round, while the owner of Momo wanted his turbocharged and the exhaust to spit flames. So I do get whacky requests, but it has to make sense. I’m not going to put spark plugs in the exhausts to get the result. I’m going to build a twin turbo like Porsche did with its 935 race car. It’s about keeping the heritage.”

The customer profile is across the board, according to Rod, with clients ranging from guys in their late 80s who’ve always wanted an Outlaw to celebrities and dentists. “It’s people who want something special or unique. They want to be part of the process, to watch the build. I send out lots of photos and people jump on Instagram to watch live streams of us working on the cars.”

Building the future

The Outlaw 356 remains the backbone of Emory’s business, but the more involved Specials are a personal draw for Rod.

“The Specials allow me more freedom to be creative,” he explains. “While they are the same as the standard Outlaw 356s underneath, there’s significantly more changes externally. They take a few months longer and are a little more expensive. We don’t do so many as they take up a lot more of my individual time – only a couple a year as opposed to eight or 10 Outlaws a year.”